>

> >

>Evolution or revolution?

It’s hardly news that the digital age has turned journalism inside out.

But did it do the same to journalism education?

Are most journalism schools revamping everything? For that matter, are they even practicing actual journalism? Are the best professors leading experimentation? Are colleges and universities using digital platforms to teach the new skills?

Yes, there are exceptions, but no, journalism education has not kept up. Surveys show journalism educators think much more of their work than does the news industry. Four in 10 graduates have figured out on their own that they did not get enough of an education in digital technology. From many thousands of educators, digital events draw a few hundred. The “Newspaper & Online News,” the largest division of journalism educators, launched its Facebook page nearly a decade after that platform’s start. It took nearly two decades for 95 percent of campus media to get onto the World Wide Web.

All this raises the big question: If schools aren’t changing quickly enough, who is preparing young journalists to cope with the newest child of the digital age, the era of mobile and social media?

No matter what you may hear, it is possible for education to change. The Carnegie-Knight Initiative for the Future of Journalism Education, a $20 million partnership between the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Knight Foundation, showed that journalism schools could teach critical thinking, subject knowledge and digital technique. Its signature program, News21, brings college students from around America to Arizona State University, to work with top professionals on a major investigative project each year. The point: journalism schools can produce work worthy of any news outlet — even the front page of The Washington Post.

If given the chance, top professionals can thrive in academia. The Knight Chairs in Journalism, which began in 1990, is a $60 million network of endowed journalism chairs. Two dozen Knight Chairs hold positions at 22 universities, where they experiment with ways to lead journalism to its best 21st century future. Knight chairs teach thousands of students and professionals each year and do journalism of their own. They connect to Knight Centers, as well as a fellowship network of Knight-funded yearlong training and media innovation programs at Stanford, Michigan, Harvard and M.I.T.

We’ve also learned that new forms of teaching can work. Poynter’s News University, built with nearly $8 million in Knight grants, has become the world’s largest digital education platform for journalism. NewsU has more than 200 interactive modules and classes, covering all skill levels and topics. Its registered users number more than 250,000.

By supporting these projects and other new ideas — the first major student investigative corps; the first entrepreneurial journalism degree; the first hybrid public-private newsroom; the first university-led digital media literacy campaign — Knight hopes to show that all institutions, old and new, big and small, rich and poor, can change.

This chapter looks at the relatively slow evolution of journalism education in the days of an information revolution. A promising exception is the “teaching hospital” model, in which professionals and professors work together to help students learn by producing effective community journalism. Yet even that model as currently practiced falls short. In the digital age, student journalism can no longer just inform communities; it must engage them. And, through experimentation and research, it must do more than just provide journalism; by trying new things, student journalism can provide knowledge about what works and doesn’t to the field of journalism.

Carnegie-Knight:

Journalism schools

can innovate

We all know the news about the news. A media policy report for the Federal Communications Commission, “The Information Needs of Communities,” has made things abundantly clear. It details the decline of “local accountability journalism.” The evidence: more than 18,000 journalism jobs lost in recent years at daily newspapers alone. This is a paradox of the digital age: more information than ever, yet less local watchdog journalism. The same communications revolution that makes everyone a potential journalist has maimed America’s advertising-based method of paying for professional journalism.

Among the initiative’s successes: Faculty connected to the whole university by team-teaching courses with other professors. Business professors helped with business journalism classes; scientists joined in to teach science journalism; arts educators, arts journalism, and so on. The journalism students learned a great deal about the subjects they wanted to cover. Their teachers gained respect for each other. When the funding ended, many of those classes continued. Tom Patterson at Harvard went on to write a book about this “knowledge-based journalism.”

The nation’s institutions of higher learning have an important role to play in the local news crisis. At conventions of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, universities are showing signs of increasing interest in local journalism. This is good news. Watchdog journalism is the security camera that keeps the powerful honest.

More journalism schools are starting to do what medical schools do with teaching hospitals and law schools do with legal clinics. A Harvard report on the Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education shows that journalism schools can help communities by playing a role in local

Journalism and mass communication education, in a nutshell, is a universe of roughly 220,000 students in 500 programs graduating 50,000 students each year taught by 7,000 faculty and 5,000 undervalued adjuncts and part-timers. Since it has traditionally took its cues from industry, as the news community in general denied and misunderstood the digital revolution, so did journalism education.

Few studies explain the important trends in journalism education, but what we have raises serious issues. Professors still debate the fundamentals. Scholars have shown that, despite “an urgent necessity,” programs are not changing rapidly to reflect the multimedia world. Most faculty members have never worked in digital media, never mind social or mobile media. Relatively few professionals get tenure track positions, and the traditional machinery to produce new professors — PhD programs — does not come close to keeping up with the nation’s diversity. Studies measuring change have failed to focus what is being required of all students, instead declaring schools have gone “digital” if they offer even one elective class in a digital subject.

Journalism education matters. Nearly 9 of every 10 entry-level newsroom hires are graduates of journalism and mass communication programs. If students are well-prepared, able to adapt to an ever-changing digital world, there’s hope. Yet many graduates emerge from schools as confused about the future as the industry itself, some 80 percent of which are not accredited by the group focusing on the field, a group that until recently did not consider technological change as a major factor in its accreditation standards.

Educators need to find ways to teach more: critical thinking, topic knowledge, and the techniques and technologies essential to a post-mass media world. The big lesson of the Carnegie-Knight initiative: it can be done. Journalism schools can indeed teach the topic expertise of “knowledge journalism” and, at the same time, practice innovative real-world digital newsgathering. Expanded, this “teaching hospital model” would attack all manner of issues. Two stand out: uniting professionals and professors in education reform and unlocking the potential of the hundreds of thousands of journalism and mass communication students to help underserved communities.

The news industry is changing its mind about the value of journalism education, according to a survey of news industry leaders in the Harvard report. Before the Carnegie-Knight initiative, news leaders were often unimpressed by journalism education. Schools were seen as unnecessary, out of touch. But today, news leaders think journalism education is improving. They said better quality leadership and faculty are essential to developing more digitally savvy, knowledgeable graduates.

In particular, they cited the efforts of the 12 Carnegie-Knight schools. They are the University of California at Berkeley; the University of Southern California; Arizona State University; the University of Nebraska; Northwestern University; the University of Texas/Austin; the University of Missouri; the University of North Carolina; the University of Maryland; Syracuse University; Harvard University, and Columbia University. All are increasing both the rigor of their teaching and their news production.

Why did the two foundations get involved? Carnegie has long been associated with higher education excellence. Knight is known for journalism education and media innovation. The two complemented each other. Carnegie’s Susan King (now a journalism school dean herself) coordinated curriculum reform grants. Knight focused on News21, designed to show that top students could do journalism worthy of the nation’s most important news organizations, and innovate at the same time.

Among the results of the initiative: new master’s degree programs in specialty journalism; curriculum reform tearing up the old “silos” of broadcast and print journalism; and student journalism appearing in The New York Times and The Washington Post, and on CNN, NBC, Yahoo, and MSNBC.

Let’s deconstruct the News21 investigation of America’s transportation system. First, former Washington Post editor Len Downie presented a seminar on the topic. Then the students went to work. Their stories revealed that scores of National Transportation Safety Board recommendations were never acted upon, endangering countless lives. Their work received more than five million page views. (Subsequent News21 probes, on voting rights and the mistreatment of veterans, were even more widely consumed.)

The Carnegie-Knight Initiative wasn’t perfect. The News21 stories are extraordinary. They set a new high-water mark for what student journalism can do. But, like nearly all professional investigations, they lacked deliberate community engagement or significant research on impact. In addition, demonstrations of curriculum reform failed to impress some small-school educators because they came from the “elite” Carnegie-Knight schools. The Harvard report contains criticism and potential remedies.

If journalism schools are to improve, university presidents must be involved. The first group of five universities in the initiative was chosen because Carnegie president Vartan Gregorian, himself a former university president, personally knew them. Gregorian believed they would contribute financially. He was right. Each of the presidents put money behind the idea that journalism education needs to modernize or become irrelevant. When the second group of seven universities was chosen (from schools with Knight-funded chairs or centers), those presidents also contributed.

“Knowledge-based journalism”

Journalism schools learned they could innovate and even develop their own tools. Partnerships sprung up between journalism and engineering schools, between journalists and computer scientists. Spin-offs were common, like all-night hackathons where participants developed new software on the spot.

All this required a new open, collaborative style of teaching, learning and doing. Journalism students learned that independence does not mean they must be lone wolves like the great writers of 20th century lore. Nor would they have to work as cogs in giant news organizations run by business people they resented. They learned to work in small, integrated teams with people from many disciplines — graphic artists, business students, computer scientists, videographers, designers, and investigative journalists. These are the teams they will form themselves after graduation as they create the small, nimble media companies of 21st century.

Best of all, they created content to benefit their communities. Before the initiative, many Columbia University journalism students produced stories that, like term papers, were seen only by professors. Today, Columbia produces live journalism through a new news outlet, The New York World, named after Joseph Pulitzer’s famed paper. The University of Southern California, inspired by News21, created Neon Tommy and more than a dozen other community news experiments, including an expansion of Spot.Us, where web site users determine what stories freelancers will do and even fund them with small donations.

At North Carolina, students told compelling stories of their own, like the one about the Alaska town that must move because the tundra under it is melting. Berkeley created special websites for underserved communities, including Richmond, a city long without a daily newspaper. Northwestern designed a news service driven from the bottom up by user interests.

The Carnegie-Knight schools are not the only ones transforming. Others among of the nation’s more than 450 college journalism programs are reaching out to their entire university, innovating, using collaborative models and providing engaging community content. We hoped the Carnegie-Knight Initiative would offer a high-visibility example of what happens when university presidents, deans, faculty and students all are interested in reform. We wanted to show what the turning point in journalism education looks like.

A study co-authored by Tom Glaisyer (now a grant-maker with the Omidyar Network) looked at content creation in America’s universities. His headline: “A lot is going on, but a lot more could be going on.”

A final round of grants in 2011 opened up the Carnegie-Knight Initiative to all schools. With Arizona State University’s president Michael Crow and dean Chris Callahan providing 80 percent of the funding, Carnegie and Knight have filled in the rest to pay for News21 for at least 10 more years. It will sport a kind of “all-star team” of student journalists. Other foundations are donating scholarship money to send top students from their states. All schools can share in the lessons of curriculum reform detailed in the Harvard report produced by the Shorenstein Center. The center also has established a website to promote “knowledge journalism” at journalistsresource.org. The site puts academic research into the hands of journalists to help increase the quality and depth of daily reporting.

We do not yet know how many universities will take reform seriously. At Indiana University, under the banner of “reform,” officials announced a plan to bury an independent school of journalism within a larger school, making it appear much less nimble. The tragedy at many schools is compounded by the fact that scores of public radio and television licenses are held by universities that claim the stations are a community service even when they air no local news at all. What if universities turned their journalism and mass communication students loose to fill that unused local news capacity? If students can cure people as they learn to be doctors, why can’t students inform and engage communities as they learn to be communicators and journalists?

By coincidence of the calendar, we occupy the earth today during a moment of profound transition in human communication. If our educational leaders do not choose to rethink journalism education now — with communities hungry for local accountability news and the world moving toward an information economy — all I can ask, respectfully, is this: When will the time be right?

This is an updated version of an article that first appeared in Harvard’s Neiman Journalism Lab.

Journalism education reform: How far should it go?

Universities can help lead the way through the era of “creative destruction” of journalism. But only if they are willing to destroy and recreate themselves.

The Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education demonstrated that change is possible. Change at the participating schools went far beyond what the foundations funded: digital-first curriculum; deep subject knowledge; collaboration and innovation; high-impact student journalism in major media, and graduates going straight into major media roles.

We did not buy those changes. Twenty million dollars seems a substantial sum. But there were a dozen schools involved over many years. In reality, our grants represented only a fraction of a percentage point of the budgets of these schools. The grants were a catalyst. We brought hope and a helping hand. The schools did the rest.

The initiative revealed four transformational trends in journalism and mass communication education, discussed below. The best schools already are living these trends. Some educators do not accept them. They argue that budgets, presidents, provosts, faculty, students, the rules — “the system” — are roadblocks to change.

So that leaves two choices: either the system really does block change, or all of that is just an excuse. If the system is blocking things, I will suggest some ways to blow it up. But if the system is not the problem, educators should help one another by sharing road maps to reform.

If colleges and universities want to ride the four transformational trends demonstrated by the fastest-moving schools, here’s what they need to do to be relevant in the future:

1. Expand their role as community content providers. Just as university hospitals save lives and university law clinics take cases to the Supreme Court, university news labs can report stories that help right wrongs. Based on the teaching hospital model, they can provide both the news and the civic engagement people need to run their communities and their lives.

2. Innovate. Journalism schools can create both new uses for software and new software itself. Anyone can create the future of news and information. Anyone includes us.

3. Teach open, collaborative methods. No longer should students be lone-wolf reporters or cogs in a company wheel. In small, integrated teams of designers, entrepreneurs, programmers and journalists, students can learn to rapidly create prototypes of news projects and ideas.

4. Connect to the whole university. This can mean team-teaching a science journalism class with actual scientists. Or creating centers with engineers or entrepreneurs. Or diving deeply into topic expertise to create “knowledge journalism.” Or, even more importantly, providing the research that drives community content experiments.

University presidents had to pay for some of this reform themselves to be part of Carnegie-Knight. Their view of journalism and communication changed. They saw the value of their schools to the wider community.

Top professionals have a critical role

Beneath these trends lie challenges and opportunities. Probably the most important one: top news professionals are as central to the task at hand as top scholars. You can’t run a teaching hospital without doctors (you shouldn’t run one with without researchers, either). Professionals and professors will need to work together in ways most have not.

Curriculum reform needs to be more than dissolving print and broadcast silos. It should redefine journalism as an intellectual activity in its own right. Call it the art of critical inquiry and real-time high-impact, community-engaged exposition and analysis. If you teach journalism merely as a skill, it becomes nothing more than a skill. Teach journalism as the most exciting profession of this century, and it becomes that.

Having been part of more than $100 million in grants to universities, I would like to offer an observation: top scholars, top journalists and top schools welcome change. Mediocre schools do not. At the top, great minds think alike. The resistance comes from the middle.

Many have championed journalism and communication school reform. A diverse, bipartisan, independent Knight Commission called for “fresh thinking and aggressive action” to deal with the digital age. The FCC’s “Information Needs of Communities” declared a crisis in local accountability journalism and asked universities to step up. A report by the New America Foundation detailed university content efforts and called for more.

With all due respect, journalism and communication education plays second chair, and sometimes first chair, in a symphony of slowness. Consider: on one side of campus, engineers have been inventing the Internet, browsers and search engines. But the news industry is slow to respond. Public radio slower still. Foundations even slower. Government slower yet again. Then come the journalism and communication schools, just across campus from the engineers who started it all. And finally, local public television stations.

Who suffers? Students, to say nothing of society as a whole. As social and mobile media were taking off, a survey showed that almost half the nation’s journalism and communication school grads were not sure the field was “very different” from the way it was five years earlier. This, when in fact there were record news company bankruptcies, layoffs, congressional hearings, new media empires as well as an explosion in new journalism techniques. Yet half the graduates were not sure communications work was very different. Who, you have to wonder, is teaching them?

Several recommendations on my wish list have to do with the growing need for top journalism professionals in the academy. We need to include exceptional news professionals in the most respected ranks of academia, the way medical schools appreciate doctors and law schools respect lawyers. The $60 million Knight Chair program, at more than 20 universities, proves this can be done. Many of these chairs are national leaders. They are chosen for their genius, not their degrees. A degree is a surrogate measure of talent, and sometimes, not a very good one.

United, the clans will discover many opportunities for collaboration. For the first time, a serious number of journalism and communication schools are experimenting. Who will study these experiments? Who will address the social science of engagement and impact? The answers will arise when we can get scholars and professionals to work together.

Certainly not digitally savvy professors like Amy Schmitz Weiss and Cindy Royal, who advocate journalism education reform and teach current technology. They are among the educators who are members of the Online News Association. Yet that group’s Facebook page in fall 2013 listed only 425 teachers when college-level journalism and communication faculty number more than 12,000. Perhaps that explains why college student media took 20 years to get onto the World Wide Web. Do the students who are unsure that change is happening get that idea from professors who also are unsure?

Society in general suffers as well. News and information is a core social need, as crucial to healthy communities as safe streets, good schools and clean air. As veteran editors like John Seigenthaler have been reminding us for generations, journalism is an essential ingredient of democracy. To that end, and because of the local news drought, foundations are stepping up their investment in news and information projects. Journalism educators could join in. Put simply, the social and mobile era offers a do-over moment for journalism education.

My wish list for what should be done is meant to provoke. Following Jack Knight’s model for a good newspaper, I hope to help educators become aware of their condition, inspire thought and rouse them to pursue their true interests.

First, journalism schools should live up to the new standards enacted by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, particularly the new flexibility in curriculum allowing students to learn more business and technology. That said, I also hope students can continue to take even more and better core journalism classes. Journalism, the nonfiction profession, should be learned by all communication students. This is even more important now because new technology allows everyone to act as a journalist.

Some of us pushed hard for

(As an aside, when I came to the Knight Foundation in 2001, we had an internal rule that only accredited schools could be considered for grants. That rule lasted about a week. A professor called. I asked: Are you accredited? “Yes.” Do you have a web site? “No.” But it’s been seven years since the World Wide Web hit. You must have had an accreditation visit. “Yes.” And no one cared that you didn’t have a website? “No.” Do you know it only takes a few minutes to create a website? “It does?”

At that moment, I thought there should be a new rule: never mind accreditation. A better rule: If the most profound change in human communication in half a millennium comes along, and you are not doing anything about it, you can’t apply for a grant. Today, that means a lot more than having a web site. It means having a good web site. It means embracing social and mobile media. It means not waiting a decade to respond to whatever comes next.)

Another new accreditation requirement calls for schools to post on the web their retention and graduation rates. That’s a start, but great schools should reveal even more. After all, they are communication schools. They should design systems that allow open, real-time reporting. Accreditation self-studies, staff technology expertise, even down to software taught or created, should appear on a school’s website. The percentage of graduates who get jobs in their field should appear at the top of the home page, with an explanation if that number is zero.

The ACEJMC diversity standard still needs expanding. It should consider all the social fault lines — gender, race, generation, geography, class and ideology. These fault lines may be relatively equal in impact, but on campus, the gender gap is the biggest. Look at how many students are women, more than 60 percent and growing. Look at how many deans are women. Is it 30 percent? Lower? Why is that number so hard to find?

Hiring and retaining top professionals

To some institutions, our professional chairs (nearly all of whom have tenure) would be unacceptable. I refer now to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the regional accreditation group with which I am most familiar. SACS is an appropriate name for a group blamed for sacking the professionals in academia.

Consider the SACS standards for hiring faculty. A university should give “primary consideration to the highest earned degree in the discipline,” the standards say. After that, “the institution also considers competence…” Also? According to SACS, the degree is primary, competence is an also-ran.

The SACS rules allow a school to argue for “unusual” or “exceptional” people. All one needs to do to defend worthy professionals without advanced degrees is provide a simple written explanation. Unfortunately, more than a few deans, provosts and presidents seem to think that is simply too much trouble. I’m sure there are stories to be told about the great professionals who were retained by virtue of cogent explanation. But we don’t hear them. We hear instead of faculty who have been unjustly demoted or fired. Sometimes, these people are so exceptional that Knight or another funder has given them a grant. Imagine our surprise when they are dismissed. Even though they are top professionals with extraordinary competence, singled out for their excellence by national foundations, they have been abandoned by their deans, provosts and presidents. The administrators say it isn’t their fault, that everyone should blame SACS; SACS says it isn’t their fault, the administrators are the ones who either defend staff or don’t.

Great professionals and great scholars are equal. They both make important contributions. But in academia they are not equal. Tenured professors have lifetime job guarantees; professionals often are hired on a class by class basis. Professors determine curriculum and sit on hiring committees. The “adjuncts” — professionals brought in to teach things faculty don’t know, often at near minimum-wage — don’t have a say in a school’s direction.

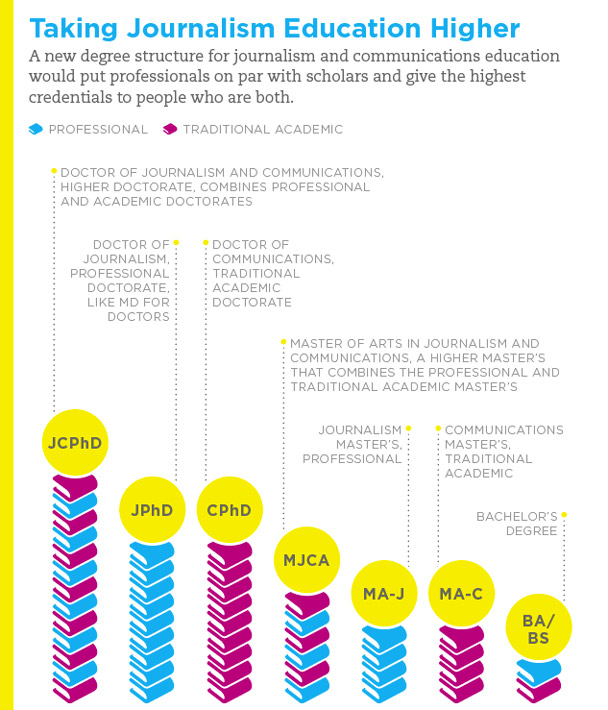

We can begin to address the inequities between top professionals and scholars by establishing a new degree structure that creates a professional PhD in journalism, just as there is a JD in law and an MD in medicine. Until then, we should recognize that “highest earned degree in the discipline,” for a professional, is a master’s. The City University of New York does it. Until there is a professional doctorate, all programs should consider the master’s a terminal degree for professionals.

We should push for all good schools to have a higher master’s — call it an MJCA — a Master of Arts in Journalism and Communications. Just as there are MFAs and MBAs, there should be a higher master’s degree for journalism. It would combine theory and practice, research and impact. Every thesis should be readable as measured by its Flesch score. Every thesis should be free and online. Before an MJCA degree is awarded, the candidate should attract significant attention to (and engagement with) his or her thesis.

We also need a professional doctorate. Call it a JPhD, a Doctor of Journalism and Communication, just as there is an MD, a doctor of medicine. To earn that degree you would need to demonstrate journalism excellence; innovation that creates new techniques, technologies, story forms or pioneering content; and, most importantly, your intellectual contribution should show community impact.

Some professionals could qualify for this type of degree in less time than it would take to get a scholarly PhD. They have spent decades in the field developing doctoral-level knowledge. But they would still need to learn how to put that work in scholarly context, show what theories it supports or debunks.

And finally, we need what the British have: a higher doctorate. This would be a JCPhD, superior to all other degrees in the discipline, a super degree. You would need to do everything the doctor of journalism and communication can do, plus everything a traditional academic PhD — call it a CPhD — can do.

The higher doctorate as well as the higher master’s grant special status to renaissance people who can be both professionals and scholars. A university pioneering this idea will need courage, because all of its current PhD holders may suddenly think they have only a penultimate degree, not the so-called “terminal degree”.

Much work remains to achieve equality between top professionals and top academics. I’m reminded of the Oregon report of 25 years ago, calling for a mix of scholars and professionals, and then “Winds of Change” 15 years ago, seeing not a coming together but a widening rift. Most notable was how so many scholars used words like “vocational,” “training” and “skill” to describe journalism, and words like “intellectual,” “scholarly,” and “peer-reviewed” to describe their work.

I wonder if scholars understand how dismissive this is. How would they feel if their chosen field was described that way? Let me try: Research without real accountability is a vocational pastime, a narrow skill applied to a limited number of jobs. Thusly seen, advanced study is an occupational degree: It qualifies you to teach and write papers, and that’s it. People who are interested in real intellectual challenges avoid PhD training.

I do not claim that the above is at all true. My intention is to show how it feels to have an intellectually rigorous endeavor — as journalism is, at the highest levels — described essentially as work for dummies. I do claim the following is true: The professor-professional gulf damages journalism education. It has become the mark of a mediocre institution when it can’t distinguish between top professionals and average ones, just as it is the mark of a mediocre newsroom when it can’t tell the difference between a good scholar and an average one.

Joining research and innovation

To be fair, the door should swing both ways. Newsrooms should embrace leading journalism scholars, twinning them with the best professionals in efforts to understand the digital world. Columbia University did just that when it placed editor Len Downie with scholar Michael Schudson to write the report, “The Reconstruction of American Journalism.”

There’s plenty to study. The “teaching hospital” model, not as it is generally practiced but as it should be, needs to produce newsrooms that more deeply understand and engage the communities they serve. In this interactive world, we need to know why some stories are debated, shared and acted upon while others aren’t. These are research topics best pursued in the living laboratory that is a working community news system.

On the positive side, some schools are adapting. They are trying new story forms; teaching data visualization, web scraping and computational journalism; developing entrepreneurial journalism programs and new software (including games), and even opening a center for drone journalism. Some are experimenting with new tools as fast as they come out. Those schools are teaching numeracy as well as literacy. They will produce better students.

Some are comfortable with “reverse mentoring,” where smart students teach professors about cutting-edge digital issues and professors teach students traditional journalism values, the fair, accurate, contextual search for truth.

Arizona State University is a good example of a school taking on the four transformational trends. Faculty there are helping students provide digital news in new, engaging ways. They are innovating content and technology. They are learning to teach open, collaborative models, and they’re connecting with the whole university. They have not abandoned quality journalism; they’ve enhanced it.

But there could be even more change. Why not teach the 21st century literacies -- news literacy, digital media fluency, civics literacy -- to the entire campus? If you have the right budgeting system, an influx of many thousands of students from other departments into yours can bring more money. At Stony Brook in New York, they are teaching news literacy to 10,000 students. At Queens University in North Carolina, they are teaching digital and media literacy to the entire community.

Money for these improvements can’t be found unless it is sought. Community foundations can play a role. For years, Knight Foundation has run the Knight Community Information Challenge, encouraging more journalism and media grant making by matching community foundations that funded local projects. But few community foundations looked to their local journalism schools for a helping hand. The Knight News Challenge looks for projects that combine news, innovation and community. It tends to hear from a small number of schools. Similarly, the department of education money for tech experiments and the broadband expansion and adoption money has not gone to journalism and communication schools, with a few exceptions, such as Michigan State. Schools might try harder to get some of those federal funds.

Once the economy recovers, we’ll be ripe for new federal program ideas. How about brainstorming something like a Media Corps, where students would get full scholarships for staying on after graduation to provide community content and help their schools transform?

Our government is doing this for the military — giving students free computer science degrees if they will serve the nation as cyber soldiers. Perhaps deans could organize and propose that the nation care for the communication of peace as it does for war.

We live in a paradoxical age. My concerns are mixed with excitement. All things considered, we should delight in the privilege of being alive at this turning point in history. Certainly, the students are enthusiastic. They continue to come in record numbers, ready to teach as well as learn, to find the new jobs wherever they are created. Journalism and communication schools find themselves offering the great all-purpose degree of the 21st century. What more can be done with that?

Pioneering publisher Bob Maynard used to say that all things worth doing begin with someone who passionately believes in them, even when others say they are not possible. He thought the moribund Oakland Tribune could become a Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper, and it did. Al Neuharth believed The Freedom Forum could create an engaging, high-tech museum of news, and now we have the Newseum. Alberto Ibargüen believed Knight Foundation could help journalism by experimenting with media innovation, and hundreds of newsrooms are using tools developed with Knight funding.

Engaging the possible requires leadership. Even if you don’t want to blow up the systems as I’ve proposed, if you passionately want reform, it will happen. To get there, you first have to get past the most difficult barrier of all, the voice in your heads that says it just can’t be done.

Transformational trends in journalism and mass communication education are beginning, despite underlying structures. That’s because people like you have decided it’s going to happen, no matter what. Blow up the rulebook if you need to. If not, please come up with better ideas. The future depends on it.

This is adapted from a speech delivered to a national conference of journalism educators at Middle Tennessee State University.

Journalism funders call for ‘teaching hospital’ model

This Aug. 3, 2012 letter was sent from journalism funders to the presidents of nearly 500 colleges:

We represent foundations making grants in journalism education and innovation. In this new digital age, we believe the "teaching hospital" model offers great potential. At its root, this model requires top professionals in residence at universities. It also focuses on applied research, as scholars help practitioners invent viable forms of digital news that communities need to function in a democratic frame.

We believe journalism and communications schools must be willing to recreate themselves if they are to succeed in playing their vital roles as news creators and innovators. Some leading schools are doing this but most are not. Deans cite regional accreditation bodies and university administration for putting up roadblocks to thwart these changes. However, we think the problem may be more systemic than that. We are calling on university presidents and provosts to join us in supporting the reform of journalism and mass communication education.

Curriculum changes have been summed up in the "Carnegie Knight Initiative for the Future of Journalism Education," a book published by Harvard's Shorenstein Center in 2011. In the “teaching hospital” part of the initiative, News21, students get special topic classes that prepare them to cover news with the help of top news professionals. This better connects journalism schools with the rest of the university, encourages deep subject knowledge and involves the teaching of digital innovation and development of open collaborative work models. Arizona State University has developed the "teaching hospital" form of journalism education to become one of the state's leading news providers.

Schools that do not update their curriculum and upgrade their faculties to reflect the profoundly different digital age of communication will find it difficult to raise money from foundations interested in the future of news. The same message applies to administrators who acquiesce to regional accrediting agencies that want terminal degrees as teaching credentials with little regard to competence as the primary concern.

We firmly support efforts by The Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications to modernize standards. The council recognizes that schools need to provide students the ability to pursue career paths as journalist-entrepreneurs or journalism-technologists.

Furthermore, we believe ACEJMC should develop accreditation standards that spotlight the importance of technology and innovation. University facilities must be kept up to date. Currently, many are not.

Journalism funders agree that academia must be leading instead of resisting the reform effort. Deans must find ways for their schools to evolve, rather than maintain the status quo. Simply put, universities must become forceful partners in revitalizing an industry at the very core of democracy.

We also agree universities should make these changes for the betterment of students and society. Schools that favor the status quo, and thus fall behind in the digital transition, risk becoming irrelevant to both private funders and, more importantly, the students they seek to serve.

The letter was signed by top representatives of Knight Foundation, McCormick Foundation, Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation, Scripps-Howard Foundation, Brett Family Foundation, and Wyncotte Foundation.

Why journalism funders

like “teaching hospitals”

As journalism funders said in their open letter, journalism and mass communication schools that don’t change risk becoming irrelevant to the more than 200,000 students and the 300 million Americans they seek to serve. Without better-equipped graduates, who will deliver the news and information of the future?

Foundations noted the digital age has disrupted traditional media economics, and that in America today, there is a local journalism shortage. Thus, the “teaching hospital” model of journalism education — learning by doing in a teaching newsroom — seems promising.

In this model, students, professors and professionals work together under one digital roof to inform and engage a community. They experiment with new tools and techniques, informed by research and studied by scholars, in a living laboratory.

The funders didn’t think the letter was controversial. Yet both the Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Education covered it as such, and the journalism educators’ convention and the listservs buzzed.

Some educators said there was no need to talk of change, that they’d already done it. But that would be impossible. We’ve entered an era of continuous change. If you changed last year, you’re a year behind. If you went digital in 2002, you’re more than a decade behind. The “we-have-changed” group includes those saying that their PhDs started out as professionals, not realizing that people who cut their teeth on last century’s newsrooms are not the digital pros we need to recruit for teaching hospitals.

Others said the funders cared only about gizmos, not content. Yet smart phones, social media and the Web are no more “gizmo” than the printing press was. They are driving a global revolution in digital content. For the first time in human history, billions of people are walking around with digital media devices linked to a common network. University programs should not claim to be digital when they aren’t using social and mobile media for news and information.

Then there are those who say they have created “teaching hospitals” when, in fact, they have not. The professional journalists are the doctors of these hospitals; the academics are the researchers; the students are the interns and residents. They diagnose and treat with stories and forums for debate. But for a teaching hospital to be complete, you need “patients.” That means not just providing real news to real people but engaging the community to be served. Students should have the experience of finding out what a community wants covered; of soliciting a community’s help in reporting; of seeing scores of comments on their stories, of finding out if the community does anything with the news, whether that news has impact. The journalism programs that claim to be “teaching hospitals” are not engaging their communities. They are hospitals without patients.

Some professors said it was “anti-intellectual” to criticize current research and call for more useful studies to help us understand the technique, technology, and principles at work in this new age. When we asked about major breakthroughs their theoretical papers had produced, or even who funds them, they fell silent. Looking back, it seems that was not the best way to start a conversation. So let’s recast the question: Can we agree we need more research that helps us understand the science of engagement and impact?

Good things are happening

College presidents from places like Western Kentucky, Washington State, and Florida International University supported our letter. Mark Rosenberg of FIU, for example, said the “teaching newsroom” is central to his new dean’s vision. It’s good to know that Rosenberg wants to build a new Media Innovation Complex (a new facility was a boon to Arizona State).

Two schools said they were looking at creating professional-track PhD programs. One is looking at creating a guidebook of best practices by the deans and directors who are good at getting tenure for top professionals. Columbia University’s guidelines are good ones. And the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications updated its standards to reflect the need for current technology and, more than that, for every student to understand the digital world.

Innovative faculty, especially younger professors, feel enthusiastic. A group of them gave a standing ovation to Richard Gingras, head of Google’s news products, when he spoke at a recent journalism education convention. These are the faculty applying for micro-grants to employ Knight News Challenge tools on their campuses.

We’ve said it before but it bears repeating: The digital age has changed almost everything about journalism: who a journalist is; what a story is; which media provide news when and where people want it, and how we engage with communities. The only thing that hasn’t changed is the why. In the digital age, good journalism (and communications) is essential for peaceful, productive, free, self-improving societies.

The best schools realize that having top professionals on hand is as important as having top scholars. “Top” is the key word: Quality today does not mean a long career or a famous name. It means you are good at doing what you do in today’s environment. You don’t have to be a big school to make a difference. Look at Youngstown, Ohio, where students are providing community content as though they were attending Berkeley, USC, Missouri, or North Carolina.

There are hundreds of hard-working deans and directors, applied researchers, sharp professors, growing numbers of digital innovators, and creative agents of change. Look at what Dan Pacheco is doing at Syracuse University, for example, or Jeff Jarvis at CUNY. To you, we say congratulations. Keep changing. We need you to keep trying new story forms; to teach data visualization; to do computational journalism; to develop entrepreneurial journalism, build new software, and even pioneer things like drone journalism. We need you to keep learning from your students, the first generation of digital natives, as fast as you teach them.

“Each and every person in this room”

No institution within journalism education has achieved all that can be achieved. Some big pieces are still missing. For example, journalism and communication schools could be some of the biggest and most important hubs on campuses. They could become centers for teaching 21st century literacy — news and civics literacy along with digital media fluency — to the entire student body. They could, but with only one or two exceptions, most of them aren’t.

The News21 project at Arizona State shows what’s possible in journalism education and why it’s important. The project’s 2012 investigation found only a tiny number of cases of voter fraud and raised questions about the tax-exempt status of the nonprofit organization that helped push states to enact voter ID laws when there wasn’t really a fraud problem. Everyone from Jon Stewart to The Washington Post used the stories. This is student work, journalism education at its finest. As Gingras said at his talk at the journalism education convention in Chicago:

“I believe we are at the beginnings of a renaissance in the exploration and reinvention of how news is gathered, expressed, and engaged with. But the success of journalism’s future can only be assured to the extent that each and every person in this room helps generate the excitement, the passion, and the creativity to make it so. May you enjoy the journey, and more importantly, might you inspire others to enjoy theirs.”

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab.

The promise and peril

of teaching hospitals

Law students file briefs, medical students treat patients, so why can’t journalism students report for the public? That’s the question considered by “The Classroom as Newsroom,” which covers the promise and peril of the “teaching hospital” model of journalism education.

Meet the News21 ASU Team from News21 on Vimeo.

For example, schools offering students this “clinical” form of education end up placing more of them into the communications job market than the national average.

As with the phrase “civic journalism,” we tend to label things to try to better describe them. Unfortunately, giving something a name can also can ruin a perfectly good idea. Some critics, for example, have picked at the “teaching hospital” metaphor, pointing out the literal differences between medicine, which requires a professional degree, and journalism and communications, which have no professional doctorate, nor any licensing. Others argue that only large, well-funded schools can have a full “teaching hospital” model, that they simply can’t do a year-round community news project.

The promise: employable students, faculty with fresh professional experience, universities providing a public service, researchers studying and informing new techniques and technologies, and communities gaining the news they need.

When students do actual journalism for a real community, their digital skills and understanding must be up-to-date. In a teaching newsroom, students learn much more about community engagement and story impact than they do by turning papers over to a professor in a classroom. They are working in a living laboratory, in a

The peril: students must be protected legally. The pace of high-pressure, year-round news production can be draining. University support, while essential, may not be there. Faculty debates over the details, including a too-literal view of the “teaching hospital” metaphor, can be an excuse to resist improvement.

We see both the promise and the peril every day. Most of the experiments cited in the “Classroom as Newsroom” have been funded by Knight Foundation. Co-authors Tim Francisco and Alyssa Lenhoff are co-directors of The News Outlet, a Knight-supported “teaching hospital” journalism experiment at Youngstown State University. Columbia University sociologist and media scholar Michael Schudson is the third co-author.

Schudson, Lenhoff, and Francisco note that the number of schools trying to do actual journalism is increasing. Still, we do not have exact numbers. Statistics kept by groups like the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication are outdated. Those need to be revamped. That said, the authors have captured meaningful vignettes.

This is simply common sense. Those who learn to shoot with live ammunition develop better aim than people only pretending to shoot. Research done by Lee Becker at the University of Georgia confirmed what professionals already knew: what employers most look for in applicants are work experience and professional work samples. If the research were done today, at the top of the list would be digital skills.

Faculty who are pure scholars without professional experience would have a tough time running such real-world laboratories. If teachers with high-level professional experience cannot be hired, or if “hybrid” PhDs (scholars with past professional experience) cannot be found, then trying to launch such an enterprise may not be wise. A teaching newsroom can be dangerous legally without libel insurance and the guidance of a top professional. This could prove even more troublesome in states whose shield laws don’t cover student journalists. The pressure and rigor of providing news on tight deadlines can be great for people who have never done it. Coping with adverse community reaction and controversy requires thick skin.

These are roadblocks. Perhaps funders should revive programs that give scholars daily experience, but this time around, locate them in the best digital-first, social/mobile newsrooms.

Parsing the metaphor

So let’s edit the metaphor. Schools with few resources might have “teaching clinics,” or even “teaching first-aid stations.” You don’t have to run a full-fledged news site to engage a community in discussion around a particular story or issue. One size does not fit all. The Youngstown experience proves that you don’t have to be a huge campus to have a teaching newsroom.

Then there’s the question of revenue. Practical journalism schools, like the one at San Francisco State University, have, for years and with no resources, offered local reporting classes yielding good student work published in local newspapers. While that doesn’t offer the community engagement and research options we want, it’s at least a start. Other examples: The University of Alabama’s “teaching newspaper” program is entirely tuition supported. The New England Center for Investigative Reporting has a variety of revenue streams, including a profitable high school journalism training program

I’m convinced teaching newsrooms will never be able to run on revenue from the news organizations they partner with. Even News21’s investigations do not receive any revenue from news organizations. In the end, the question is not whether a program is expensive or no-cost, but whether it is the right size for your campus.

Many debate whether student journalists should be paid. That frame may miss the point. My youngest son plays French horn for the college orchestra, as well as the basketball team’s pep band. He gets credit for one and money for the other. My oldest son freelances as a graphic artist for pay. He works for a tech startup for equity. When he was in school, he created art for credit only. The form of compensation isn’t the point; what matters is there is compensation with real value. When you learn amazing new things, that’s value.

In “The Classroom as Newsroom,” the authors provide useful advice about balancing classroom and newsroom to be sure academic value is there. I think that’s the main thing: pay should not be a surrogate for educational value. Perhaps the kind of formal evaluation the authors call for can be directed toward this question from the student point of view. I’d also look at what knowledge these projects are providing to the field of journalism. If student journalism serves only to replace the work of laid-off local journalists, an opportunity to improve journalism and journalism education will have been wasted.

The most encouraging aspect of Lenhoff and Francisco’s work is their community engagement effort. Too many student news services are one-way, assembly line news factories that spit out stories. That is (as the students say), so 20th century. Today, engagement is crucial. When hundreds of millions of people each carry a powerful mass media device in their pocket, local producers of news must know not only how to reach them, but how to interact with them. Giving students real news experience also gives them real community experience. The relationship between engagement with the news and the impact of the news is a vast new area for formal study. Scholarship may well prove what my colleague Michael Maness, Knight vice president of journalism and media innovation, says: Human-centered design of news products and projects is a key to engagement.

The most important factor in the success or failure of the teaching newsroom model may well be the support of a university’s president. If the president is behind the idea, money flows and doors open. That said, success can’t happen without the right faculty, people willing to keep costs down by tightly integrating the journalism with the teaching.

The digital age heralds a time of continuous change. New forms of communication are being created faster than PhDs can be minted. Who has a doctorate in the social implications of 4G smart phone? What schools have integrated mobile media into most or all of their classes? Getting a doctorate or getting a new class through the bureaucracy (which some call a “blood sport”) can take years. We need more flexible systems: Classes in “the new thing,” and that new thing can always change. Doctorates that look at technologies being invented on the other side of campus, not what’s already here.

Extraordinary professionals, those meeting high intellectual standards, can help journalism and communication schools develop greater clinical expertise. Professionals co-exist with scholars in law and medicine. They co-exist in art and music and business schools. They could do so in journalism as well. When they do, students and professors might be helping invent the future of news.

This article was part of an online package posted by the International Journal of Communications.

A problem with academic research into journalism?

Much has been written of late about the relatively low quality of academic research in the journalism and mass communication field. This is a critical time in communications, and so, there’s much to study. The research gap is a major source of disagreement between professionals and scholars. Professionals argue that much research is unreadable and, frankly, useless. Scholars counter that if you take the time to read the stuff, you’ll find important insights.

Another way to track citations is through Google Scholar, which confirmed relatively low numbers of citations on individual articles in the three “journalism” journals. In addition, the chart below, from SCImago Journal & Country Rank, shows that every year, at least half the Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly articles remain uncited. The latest year on record shows no citations for 69 percent of the articles. Remember, the Quarterly appears to be the best of the three AEJMC “journalism journals.”

Someone has to ask: Is it really wise to base tenure and promotion on journal articles that are never cited? It’s difficult to imagine working journalists promoted for writing stories no one ever mentions.

Valiant educators over the years, such as Del Brinkman (formerly of Knight Foundation), and currently, Michael Schudson of Columbia University, have tried to find and translate important scholarly work in journalism. It is tough slogging. The most quoted journalism notion in the past decade (one that media mogul Rupert Murdoch popularized in a speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors), did not come from a journalism journal of any type. It came from Marc Prensky, who coined the term “digital natives,” and asked if they really think differently than the rest of us.

Why do we care about research at all? It’s important to the future of journalism education because publication in the so-called peer-reviewed journals traditionally has been the number one criteria for faculty promotion and tenure. Yes, when it comes to job advancement, research beats teaching.

In the professional world, journalism that makes a difference is measured by impact -- by the unjustly imprisoned freed; the criminals jailed; by the new laws or policies that save lives or stop government waste. In universities, this “community service” (as it is called) is not given the importance it deserves. Publishing in academic journals is what counts, even if those journal articles do nothing to further how journalism serves America. (See the blog post by University of Southern California’s Geneva Overholser about “what’s missing” in the debate about journalism schools.)

Let’s look at three journals, each with the word “journalism” in its title, each widely touted by the nation’s organization of journalism educators. Yet citation research -- tracking how often scholars quote each other-- raises provocative questions about these three. Not one ranks among the most cited or prestigious of the journals in the communications field, nor in the social studies field at large.

For this comparison we used databases built by Thomson Reuters, which tracks thousands of journals and citations. All three journals in question are published under the auspices of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication: Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Journalism & Mass Communication Educator and Journalism & Communication Monographs.

To qualify inclusion in the “Web of Science” database, Thomson Reuters considers: 1.) The journals’ publishing standards; 2.) Editorial content; 3.) International diversity, and 4.) Correct metadata. A journal that has never been cited, for example, would not be picked up by Thomson Reuters.

Of the three, as of last year, only Quarterly had been selected for inclusion, and to receive a Journal Impact Factor in Journal Citation Reports. Educator had been rejected in January 2010 but was up for re-evaluation. As of this writing, Monographs also was “under evaluation.” Considering their long lives, a spot-check showing only one of the three

We checked the Quarterly against all the communication journals in the dataset. Given how much the journal produces, not much of it was cited in 2011. The Journal Impact Factor ranked Quarterly number 48 among the 72 communication journals. Considering the importance journalists place on their profession as the “bedrock of democracy,” being in the bottom 50 percent is, again, troubling. Of the 2,943 social science journals, Quarterly ranks 1,950, according to impact measure. (The Journal Impact Factor, Thomson Reuters says, can be “used to provide a gross approximation of the prestige of journals to which individuals have been published.”)

Does this mean a conspiracy against communication journals? Do social scientists simply not like journalism or communication? Hardly. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking (first out of 72 communication journals when ranked by Journal Impact Factor) ranks in the top 10 percent of all social science journals, again using 2011 citations. Note the words cyber and social networking in the title.

Research papers seldom cited

This is disquieting, given the more than 7,000 full-time and more than 5,000 part-time professors who should be reading and quoting each other (even if none of the scores of thousands of scholars in other fields find journalism interesting.)

This also doesn’t seem fair to good scholars. Why is the saying “publish or perish”? Why would a scholar who writes dozens of articles no one cites be considered in any way equal to a professor like Mark Deuze of Indiana University, whose media work and daily life research is cited by hundreds, or participatory culture rock star Henry Jenkins of the University of Southern California, who is cited by thousands?

At its 2012 convention, the Association of Educators in Journalism and Mass Communication gave out a thumb drive with the “best” scholarly articles from decades of the three journals in question. Too many of them seemed derivative, obvious or obtuse. To quote a senior journalism educator: “There are three categories of research these days: 1. Who cares? 2. No shit! 3. I don’t have any idea what you are talking about.” To be generous, perhaps we should add a category: “4. Needs more work, but there might be something there.”

Some of the “Research You Can Use,” listed on the AEJMC website, seemed to fit into category 4: the social responsibility of news organizations, gatekeeping, agenda-setting and “framing” all seem meaningful. But through the lens of social and mobile media and its attendant participatory culture, only such classics as Marshall McLuhan’s “Media is the Message” and Walter Lippmann’s “Public Opinion” appear to hold their own. Yes, Lippmann was right; media still gives us a picture of the world; and yes, McLuhan was right, media type still affects content. A lot of the rest just feels out of date.

When no one cites a paper, questions can be raised about research topics and quality, but a zero probably should not be considered an absolute indictment. Perhaps no one reads that journal. Or perhaps the research is good and other scholars saw it, but they just don’t care. A case in point may be “Bridging Newsrooms and Classrooms,” by a team of six doctoral graduates of Indiana University, who in 2006 warned that journalism education was going to be in a world of trouble if it didn’t speed up its digital transformation. “Some scholars doubt whether journalism school professors are theoretically and especially technologically prepared,” it said. Yet the need for reform is “an urgent necessity.” Only 56 percent of the educators surveyed were even talking about curriculum change. The paper only received about 50 citations, according to Google Scholar. Fifty is certainly better than zero. Yet the topic directly touches every other scholar in the field. Shouldn’t more than 50 of the 12,000 faculty in journalism and mass communication schools be thinking and writing about the future of journalism education?

Research tough to translate

Schudson, for one, believes that journalism studies research, while not "particularly strong," is still "vastly stronger" than it was 20 years ago. Still, he says, the journals he most depends on are not the ones published by AEJMC. Schudson’s list includes Journalism, out of The University of Pennsylvania; Journalism Studies, from Cardiff; the International Journal of Communication, from USC, as well as Political Communication, the International Journal of Press/Politics, and Media, Culture and Society. Professionals hoping to learn about the field might try some of the journals Schudson lists. Good researchers from places like the University of Missouri, the University of North Carolina and elsewhere produce important work that often ends up in these sorts of journals.

How do the editors of the AEJMC journals react to being ignored, in relative terms, by other scholars? From what I’ve seen, their conclusions are: we don’t market well enough, we don’t get enough funding, and some articles aren’t meant to be quoted. (Scholars have created a category of articles “not meant to be cited,” which cuts down on the sting of more than half the articles in a given year not cited at all.)

We wrote Dr. Daniel Riffe at the University of North Carolina, editor of the most-cited of the three journals touted by AEJMC, the Quarterly. We asked:

1. What do you think of citation studies — specifically the Thomson Reuters impact scale -- that rank the Quarterly 48 of 72 in the communications field?

2. The SC Imago Journal and Country Rank, from the Scopus database, says nearly 70 percent of the articles in the Quarterly are not cited at all. If that is accurate, why?

3. Are journal citations in general a good measure of the quality of a journal? Why or why not?

4. What would you say to those who argue that the quality of the Quarterly and the AEJMC journals should be significantly improved? If that needs to happen, how could that be done?

5. Is there any piece of research — cited or uncited — that you think proves the value of the Quarterly in its mission of keeping up with the latest developments? Are there, for example, any of the AEJMC-cited “Research You Can Use” items that are especially illustrative?

Riffe, who is the Richard Cole Eminent Professor at UNC/Chapel Hill, said he would answer as soon as time allowed, but noted his journal work is “on hold” due to teaching demands. Six months later, at the writing of this update, he still had not replied. I am told Riffe is a fine scholar, one of the better ones. I include the questions merely to show that we tried to get an explanation from the most-cited of the AEJMC journals.

While we’re waiting, here’s some advice from America’s great early journalist, the writer and statesman Benjamin Franklin: “If you would not be forgotten as soon as you are dead & rotten, either write things worth reading, or do things worth the writing.” Scholars, take note, when you next hear of your students setting aside traditional journals as they look for intellectual reflections and philosophical road maps on the future of journalism. No one can blame them for going to the Project for Excellence in Journalism, Nieman Journalism Lab, the Poynter Institute, PBS Media Shift, the Tow Center at Columbia, the Shorenstein Center’s Journalist’s Resource web site and other places where scholars and professionals work together.

For a follow-up in The Philadelphia Inquirer, two leading journalism educators told me they agreed professors and professionals should join forces to study digital journalism experiments.

Said Jerry Ceppos, former Knight-Ridder company news executive and currently dean at the Louisiana State University Manship School of Mass Communication: "For starters, I would gently say that professionals could improve the accessibility of some writing and even graphics without reducing the gravitas of articles. After all, that's what professional journalists do. In addition, research areas suggested by professionals might help the journalism industries — again, without reducing the quality of content."

Jean Folkerts, professor and former dean of the school of journalism and mass communications at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, agrees. "By doing the research together, [scholars and professionals] inform each other and learn from each other. Such collaboration ends the vicious cycle of academics believing that journalists jump to conclusions without adequate data, and of journalists thinking academics have no regard for journalistic work."

So what are we waiting for? Unite the tribes. We need everyone's help to bring high-quality journalism into the digital age, to perfect new ways to keep independent news and information flowing. We need a better understanding of the "science" of how news informs and engages communities.

Demand Grows

for Digital Training

Can journalism schools expand their impact and reach through more distance

The Knight Chairs noted that some journalism schools do offer online master’s degrees as well as one-off on-line courses. They said that while schools should do more e-learning, they are not doing enough to define best e-learning practices. Many educators have an outdated idea of e-learning, they said, thinking it is little more than a lecture on-line. Howard Finberg of the Poynter Institute had a possible solution: Create e-learning modules for teachers and trainers who want to learn how to create good e-learning.

Rosental Alves, Knight Chair in International Journalism, pioneered e-learning at Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, which over nearly a decade has trained more than 6,000 journalists in Spanish and Portuguese. E-learning, he said, has two distinct advantages: the courses are low cost and self-directed modules can be taken at any time. Alves next experimented with MOOCs (massive open online courses), and found he could reach more than 6,000 journalists with just two classes.

The study “Digital Training Comes of Age” surveyed 660 journalists who took Knight-supported training programs. The survey showed that online classes are gaining popularity as a cost-effective way to reach more trainees. A third of U.S. journalists and eight in 10 international journalists say the online classes they took were as good as, or better than, conventional classroom training. Demand for training continues to grow. More and more, journalists want digital training, such as multimedia and data analysis. Most give their news organizations low marks for providing training opportunities.

The report also includes case studies showing the impact of training. Participants said that professional development helped them learn multimedia skills to create new, engaging story forms; provided entrepreneurial skills needed to start new local news ventures; taught university professors digital fluency needed to teach the latest best practices; and helped journalists investigate wrongdoing and prompt policy change.

Knight Foundation has invested more than $150 million in journalism education and training over the past 10 years. Each year, Knight grantees, including two-dozen Knight Chairs at leading universities, teach and train thousands of journalists of all ages.

The report calls the digital age a “do-over moment” for the news industry, which has historically lagged in professional development for its employees. In the past, the cost of quality training was an obstacle news executives bridled at. Now, training of all kinds can be done online at lower cost to newsrooms and more convenience to employees.

This is good news for Knight Foundation, which has tracked newsroom training in studies published in Newsroom Training: Where’s the Investment? and News, Improved. A decade ago, our $10 million Newsroom Training Initiative tried to increase news industry investment in training. With projects like Tomorrow’s Workforce, NewsTrain and News University, we could see we had increased training. But industry investment still lagged. Before the initiative, only a third of the news organizations we surveyed thought training budgets should grow. After the initiative, no change. Yet learning organizations are the ones most likely to survive the digital transition.

“Digital Training Comes of Age” noted: “The good news is that the reset button has never been easier to hit, nor has it ever been more powerful. The digital age has made it simpler than ever for modern day journalists to teach their peers. By putting the sum total of human knowledge at the tips of our fingers, the Internet has opened up better ways of sharing and using that knowledge. There’s more to learn, but teaching is easier.”

This blog followed a presentation for the Knight Chair luncheon in Chicago at the convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

A survey from the Pew Research Center, “The Impact of the Internet on Institutions in the Future,” reinforces the idea that academia is the next e-learning frontier. By 2020, Pew said, student and parent demand will be so great that e-learning will blossom.

Let us know what you think

Site directory

Site directory Learning layer directory

Learning layer directory