Many roads to change

Not everything a foundation does is conceived as a major initiative. Between 2003 and 2012, Knight Foundation made more than 650 journalism and media

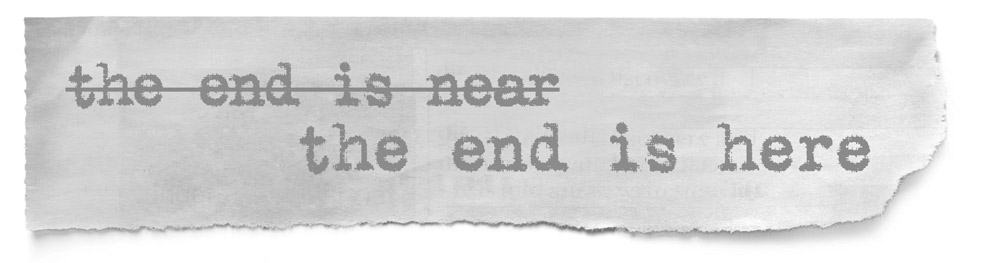

This, the final chapter of Searchlights and Sunglasses, looks at things still simmering. (You can explore the work of our grantees at knightfoundation.org.) Will all the news community’s projects succeed? No. In fact, the more we venture into the unknown, the higher the risk, the greater the chance of failure. As in science, though, experiments are not really failures if you learn from them.

The best part of this work is seeing the modest turn to the transformative. Just two examples:

With the American Society of News Editors and the Radio and Television Digital News Association, Knight funded a major youth journalism initiative. Its SchoolJournalism.org portal inspired the creation or improvement of thousands of middle and high school media outlets, helping re-ignite secondary school journalism in the U.S.

With the Associated Press, newspapers nationwide and many others, we created Sunshine Week. That national campaign provides an annual status report on the state of freedom of information, aimed at that those who use open government laws — for the most part, not journalists, but citizens themselves. Sunshine Week seems to have helped slow the never-ending attempts to roll back freedom of information in the U.S.

Today, we continue to promote new digital tools and best practices through media innovation programs, endowed journalism training and teaching programs. Here’s a kind of crazy salad of issues I’ve been thinking about lately: digital media literacy, including First Amendment education, IRS nonprofit media rules, a collaborative challenge fund for “teaching hospital” experiments in journalism education and, last but not least, clear writing.

Of those, let’s look at two:

Some may say we should not be so ambitious. But that isn’t the Knight way. In the early 20th Century, after Jack Knight inherited the Akron Beacon Journal, he and brother Jim built it into what was once the biggest (and many would say best) newspaper group in the country. Later, Jack said he really didn’t inherit a newspaper, he inherited an opportunity. That’s all any of us have: the opportunity to try.

How much comfort news

is in your information diet?

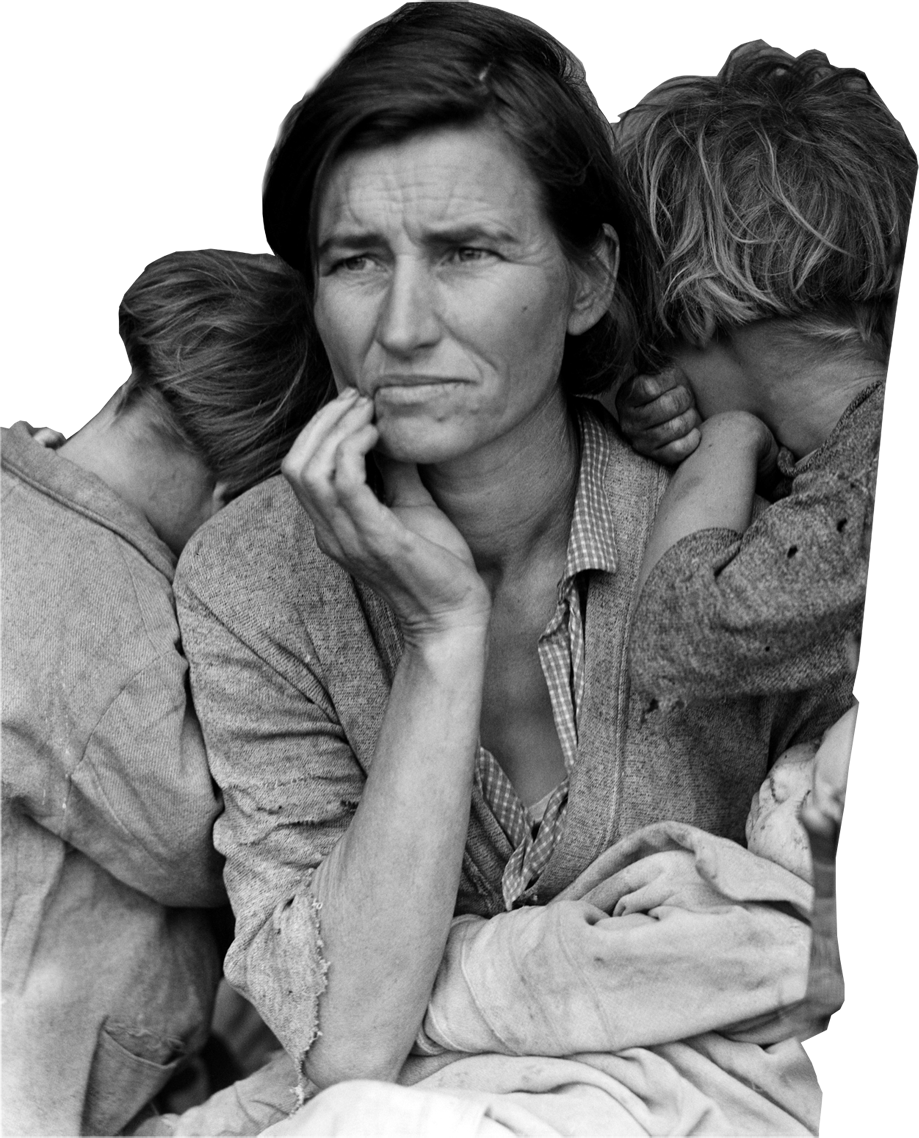

We the people are fat. So much so, medical experts have declared an obesity epidemic costing this nation untold billions. There’s an even bigger epidemic out there, less obvious, but no less dangerous. Just as we consume too much comfort food, we are, more and more, consuming “comfort news.”

I’ve mentioned comfort news before, but it deserves a fuller explanation. You are on the Internet, listening to talk radio or watching cable TV. You say, “HEY, I agree with that guy!” — and you feel good. But how much protein, how much fact, is involved? Are you getting real news, or an opinion pretending to be news?

Comfort news is the brain candy of the news stream. Like comfort food, it brings temporary pleasure. Yet if we consume nothing else, society pays the price.

Yet we also complain — as did half the people in Chicago during a poll by the Chicago Community Trust — that we don’t know enough to vote. I’d wager the newsless of Chicago haven’t checked websites like Project Vote Smart. It’s easier for us to blame “the media” than it is to change our own news consumption.

We share comfort news within our like-minded circles to convince ourselves something is true when in fact it may not be. Both conservatives and liberals do it. It’s the reason the political blogosphere has separated into two giant groups that do not link to each other. It’s why so many conservatives can’t accept the scientific evidence that humans are causing climate change. It’s why so many liberals can’t accept the data showing Americans have more guns than ever, but, in recent decades, violent crime has fallen. Comfort news is the reason why we know so much about celebrities and so little about what our government does or how to solve our most pressing problems.

This trend is the underbelly of the information revolution.

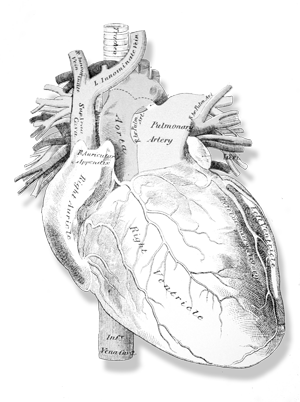

What food does for the body, news does for the mind. We need food every day to live. We need news and information every day to function in a free society.

Both the food and news systems are shaped by markets, technology, personal choice and public policy. Just as some people prefer to grow their own food, some prefer to blog their own news. There’s a crusade against national fast-food chains; there’s a crusade against fast-food news. People talk about organic, homegrown “slow food,” and they’re starting to talk about carefully produced, unrushed “slow news.”

Like modern agriculture, modern news technology offers an amazing array of choices. Used badly, however, it can amplify our worst tendencies. Some scholars, including Ralph Lowenstein, dean emeritus of the University of Florida School of Journalism and Communication, saw it coming. Forty years ago, he warned that interactive electronic news could lead people to surround themselves in "a political, social or educational cocoon. “When that happens,” he wrote, “society will suffer, since it is likely to be divided into highly polarized and probably unempathetic people.”

Polarized? Unempathetic? Welcome to 21st century America. We have healthy food, but we often choose to eat the other. We have good journalism, which as I say is based on FACT — the Fair, Accurate, Contextual search for

Eli Pariser’s best-seller The Filter Bubble documents our retreat into our own little entrenched worlds. Every day, media and technology companies are finding new ways to help us block out the things we don’t want to see and hear. Search engines remember our clicks and serve us more of what we like. In this era of information overload, 70 percent of us say we are overwhelmed. So we welcome those filters, using whatever digital sunglasses we can find.

Comfort news undermines civic debate

Too much comfort news is as bad for the

The solution: pay attention to what we feed our brains. Stop blocking out so much of the world, and take in some informative fruits and vegetables along with the sweet stuff. Make ourselves uncomfortable once in a while by seeking out facts that do not mesh with our opinions. Try going on a news diet, where we limit those news carbs. If we created our own South Beach Diet for news, what would that look like?

This is easier said than done, of course. It isn’t just a question of willpower. The stresses of modern life lead to its excesses. We develop coping habits that are hard to break. While knowledge alone can’t solve the problem, it is an important first step. To be a first-class citizen in the digital age, you need digital-media fluency. The Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities concluded that digital media fluency should be taught at all levels of education. But there’s even more to it. Knight invests in journalism excellence (the art of making important news interesting). We push for journalism education and public media reform, helping legacy institutions learn new ways to inform and engage with communities. We work to accelerate media innovation so that the best of the news and information humanity has to offer can be easily created, found, used, and shared.

The foundation believes that a healthy flow of news and information is just as important to communities as healthy air or water.

Yet we’re under no illusion about who drives media consumption. We the people do. We get the media we demand, the media we deserve. More and more, we are the media. Recognizing media consumption trends could kick start a host of new self-help groups: Comfort Media Anonymous, America Unplugged, you name it.

In the end, what’s true for food is true for news: we are what we eat. As Knight Chair and food journalist Michael Pollan says: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” When you think of your information diet, try this mantra: “Consume news. Not too carelessly. Mostly facts.”

This is an updated version of an opinion column that originally appeared in The Miami Herald.

Would nutrition labels

work for news?

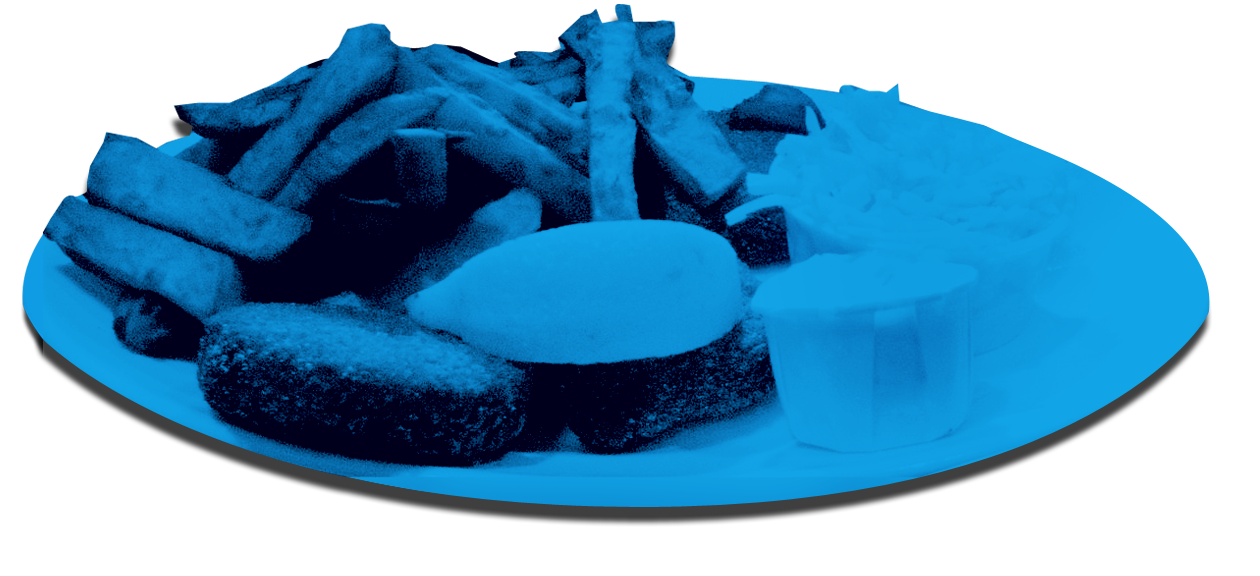

Matt Stempeck, research assistant at the MIT Center for Civic Media, once asked the question: “What If We Had a Nutrition Label for News”?

Good question. Anyone who can break down and communicate the nutritional value of news will be an American hero.

In a free press system like ours, it will never happen, but it’s both fun and educational to imagine a nutritional label on each news story. This spins off of Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer's observation that the new unit of organization of news is the story, not the news outlet. Instead of buying a newspaper to get the package, everything that’s in it, we search the web for a single news story that we really want to see.

Let’s say we agree that great journalism is the fair, accurate, contextual search for

Breaking it down in this way would do for news nutrition what labeling has done for food nutrition: make it something consumers can understand.

Knight Chair Michael Pollan has pointed out that while we have had food labeling for a long time, we have in a sense negated it by allowing companies to market their products with flashy packaging that makes false food appear to be real. During the Nixon administration, a rule was dropped that had required the use of the word “artificial” on packaging of products that were not real food. The result: an explosion in processed foods. The slogan appeals to our feelings, the label to our intellect. The obesity epidemic suggests a lot of people don’t make it from the front of the package back to the label. Pollan says, even those who read nutrition labels are going down the wrong road if they focus on vitamins without thinking about whether the food is actually the real stuff from the natural world the human species always has eaten.

We’re reminded, then, that information, while essential, may not by itself change behavior. You can't just inform, you also have to engage. In “Switch: How to Change When Change is Hard,” writers Chip and Dan Heath popularize the metaphor of a person’s decision-making system being like a rider on an elephant. The rider is the thinking mind; the elephant is the emotional mind. When your rider wants to go one way but your elephant wants to go the other way, guess which way you go?

The Heath brothers say the secret to change is to find ways to reach the elephant. In West Virginia, this was done in a successful billboard campaign showing how much fat was in whole milk by using a giant glass of milk, an equals sign, and five strips of bacon. Consumption of non-fat and low-fat milk increased.

What would that billboard look like, if it were focused not on food, but on news?

This article originally appeared in the Knight blog.

Little rules that created

a big problem

Funders, nonprofit journalists and academics gathered awhile back to discuss the challenges nonprofit news outlets face in getting charitable 501c3 status. The gathering was part of a project called the Nonprofit Media Working Group, a partnership between Knight Foundation and the Council on Foundations.

The group is chaired by Steve Waldman, senior media policy scholar at Columbia University. Waldman was the lead author of the first major government report in a generation on the state of local news. Among the findings of that FCC report was that IRS nonprofit media rules appear out of date, and thus are unhelpful to the growing field of nonprofit news outlets.

An HDTV segment from Dan Rather Reports outlines the story of Public Press, a small San Francisco news outlet that has been seeking nonprofit status for more than two years. (That particular story had a happy ending: Finally, after a 32-month wait, SF Public Press did receive nonprofit status.)

The Rather segment reported the growth of nonprofit media. It speculated that the IRS may be confused or overwhelmed by nonprofit digital media requests. Rules under which the IRS grants nonprofit media status, the segment noted, were created long before the Internet. So it’s a reasonable guess that the tax rules, like those of so many other institutions, just haven’t adapted to the digital age.

Still, Rather’s story did not interview any IRS officials. The IRS issued a statement saying it could not comment on specifics of any single case, but that “novel” applications get special consideration. Later, however, a scandal erupted when IRS officials were found to be singling out some groups for special scrutiny. Given the incomplete IRS response, it’s also a reasonable guess that the words in nonprofit media applications, such as “being a government watchdog,” could have gotten those thrown in the scrutiny pile. Regardless of the reason they were set aside, however, the old nonprofit media rules became the justification that the IRS used to delay or deny the applications.

Why is this important? At Knight Foundation, we think news and information are core social needs. Our bi-partisan commission said we need new thinking and aggressive action to increase both information flows and community engagement. Knight has been involved in hundreds of experiments to do just that.

Waldman’s follow-up study at the Federal Communications Commission, named Information Needs of Communities, detailed the loss of more than 15,000 journalism jobs in recent years, nearly all local. The study concluded that this amounted to a crisis in “local accountability journalism,” the journalism producing news we need to run our governments and our lives.

The FCC report pointed to nonprofit tax regulations as unfriendly to new media models. At the same time, there were several publicized cases of 501c3 status being long delayed. So Knight funded a working group with the Council on Foundations to look into the issues the report raised. The group asked: Are the rules being misunderstood? Are there confusing or contradictory regulations that need clarifying or updating? Does the underlying law need addressing?

With all this as a backdrop, a panel chaired by Waldman looked at the nonprofit media questions. Working group member Cecilia Garcia, then of the Benton Foundation, said the nonprofit sector must play a larger role in media, but that foundations by themselves can’t sustain nonprofit news. Kevin Davis of the Investigative News Network noted that in-depth journalism has been cut more than other forms, because, as a rule, it is not profitable. During INN’s long effort to get charitable status, it had to strike the word “journalism” from its mission statement, and agree to operate at a “substantial loss” (not making a profit wasn’t good enough for the IRS).

Marcus Owens, attorney for the working group, from Caplin & Drysdale is a former IRS official who once oversaw nonprofit applications, including those from media organizations. He noted that the original nonprofit rules reached back to 17th century English law to define what is charitable. Public “education” projects may be charitable. Though journalism projects meet that definition of educational in the rules, for some reason the IRS does not automatically believe they are educational. (So much for Henry Ward Beecher’s 1873 pronouncement: “Newspapers are the schoolmasters of the common people.”)

The major issue, Owens said, is the part of the rules saying nonprofit media need to be produced differently from commercial media. That’s why the IRS has questioned nonprofit revenue generated by ads, subscriptions and syndication. Since commercial media depends heavily on those sources, the logic goes, nonprofit media should not. That might have worked fine in the 1960s, when nonprofit media did not look like daily newspapers. But it’s incredibly outdated in the digital age.

As it deliberated, the working group did find that these distinctions are not valid in an era of collapsing ad models and, indeed, the convergence of for-profit and nonprofit business models. In the digital age, can you really tell the difference between a sponsor, an underwriter, an advertiser and a marketing partner? The important point is that the rules allow nonprofit media to collect “unrelated business income,” and when they do, it can be taxed. So agents should not be telling nonprofit media applicants that advertising is not allowed.

Garcia said foundation money alone can’t bridge the local “market gap” left by commercial media. Foundations (including Knight) often urge nonprofit media to be entrepreneurial. “Once we seed an organization,” Garcia said, “there needs to be a systematic, strategic way to replace our funds.” Local media need local support. Their relationships should be with their communities, not with faraway funders.

Nonprofit news organizations need multiple revenue sources

Joel Kramer, a working group member whose MinnPost has become a model of successful nonprofit news, said his $1.5 million revenue includes 25 percent from advertising and sponsorship, and only 20 percent from foundations. He also draws revenue from events, syndication and other sources. A diversity of revenue sources, Kramer said, is crucial to nonprofit media success.

Kramer and other panel members thought it would be better for the IRS to stick to the basics: nonprofit news status should hinge on whether a news outlet benefits the community rather than shareholders, and whether it provides news and information that adds to our common knowledge on matters of public interest.

The working group’s report concluded that the rules were indeed outdated. The FCC’s chairman supported it with a statement. A group of deans from leading journalism schools agreed. Celia Roady of Morgan Lewis, and other lawyers in Washington, have recommended the IRS and Treasury Department update the rules. All of the above, plus the full list of working group members, can be found at this Council on Foundations web page.

I think we’re making progress. Still, it’s deeply disturbing that the IRS rules governing nonprofit media applications are not just old, they are 50 years old. How many other regulations have been made obsolete by the digital age? How long will it take for society to catch up? What is that costing us?

: The working group seems to have made a difference. The IRS has approved all the news organizations singled out in the group’s report, and some 20 others. Since the outdated regulations can still be evoked in the future, however, the Council on Foundations still hopes to change them

A First Amendment example

We’ve done a string of studies about First Amendment education in America’s high schools. The following sketches out what our “Future of the First Amendment” surveys — 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2011 — have been saying. Initially, I had seen First Amendment education as a school issue. Now, I think young people can learn about the nation’s five fundamental freedoms outside the classroom as easily as they can inside. Maybe even more so.

This research started in a roundabout way. After the 9-11 terrorist attacks, support for the First Amendment among adults dropped significantly. In 2002, the First Amendment Center’s annual “State of the First Amendment” survey reported that 49 percent of adult Americans thought the First Amendment went too far in the rights it guarantees. Suddenly, America’s fundamental freedoms seemed to be up for debate. At the time, Knight Foundation’s journalism program had a high school journalism initiative. So we contacted the survey group used by the First Amendment Center and proposed a new version of the survey — for America’s high school students, teachers and administrators.

The core of the survey covered the basics. What do school folk and their students know about the First Amendment? Did they care about the 45 words that give Americans the right to say nearly all other words? Each survey asked core questions on freedom of religion, speech, the press, assembly and petition. We also added new questions to probe why students believe the way they do.

2004: More than 100,000 students, teachers and administrators took the first survey. The results revealed a surprising lack of First Amendment understanding and appreciation in high schools. Three-fourths of the students said they either didn’t know or care much about the First Amendment. This news made national headlines. Liberals and conservatives alike agreed: something should be done.

A bright spot: students who get First Amendment teaching in schools know more about it than those without classroom instruction. In addition, student journalists, who get even more instruction, have a larger understanding and appreciation of the amendment. A lot of people, including me, thought it reasonable to believe that increased teaching would help move students toward a better understanding of and appreciation for the First Amendment.

2005: Congress created the annual Constitution Day, requiring public schools to teach about the Constitution every year on Sept. 17, the anniversary of the 1787 signing.

We invested in teaching and resource programs, trying to put a First Amendment focus on Constitution Day. Grantees, including the Bill of Rights Institute and the Newspaper Association of America, distributed classroom materials. Channel One produced news stories and video lessons. We reached some 40,000 teachers. Our experiment hoped to show whether the combination of news stories about the survey, the Constitution Day mandate and new teaching materials might increase First Amendment teaching and learning.

2006: Our second survey showed that teaching of First Amendment issues increased significantly. Yet students seemed to be going in the wrong direction. More students this time around said the First Amendment goes too far — 45 percent, up from the first survey’s 35 percent. Perhaps many of the teachers who had recently started teaching the First Amendment weren’t very good at it. The teachers who had low opinions on freedom tended to pull the students down to their beliefs. On the other hand, teachers strongly supporting individual rights helped bring the students up.

In other words, the increase in teaching did not equal increased learning. We started to question the idea of Constitution Day-style solutions. We wondered about other ways students could learn about the First Amendment. After all, the public seemed to like the First Amendment again. (By 2006, the percentage believing it “goes too far” had fallen from 49 percent to only18 percent). Some scholars claimed (wrongly, it turned out) that young people didn’t care about public life, so out-of-class lessons just wouldn’t work. The team working on the research realized it didn’t know enough. We wanted to know more about the power of Constitution Day, who influences young people, and whether they consumed news.

2007: Our third survey showed that Constitution Day had not been observed in schools as much as we thought it was. Teaching of First Amendment issues was falling off. But student support for the First Amendment increased. The survey also showed that parents, not teachers, have the greatest impact on young people’s news choices. Students were indeed connected. But they consumed news digitally rather than traditionally. So the journalism team thought out-of-classroom projects might move First Amendment numbers forward.

By this time, many of our grants to increase teaching were running their course. We did continue to help education reformers like First Amendment Schools founder Sam Chaltain produce teaching materials and books through his Five Freedoms Project. But we worried about the difficulties of trying to reform the nation’s educational system. America’s largest foundation, the Gates Foundation, had put out a report on its massive high school reform efforts, detailing how complex, expensive and difficult education reform can be. We continued to wonder what, if anything, could happen outside the classroom that might help the First Amendment.

2011: Our fourth survey showed that high school students who used social media had greater First Amendment knowledge than those who didn’t. In the midst of the social and mobile media revolution, for the first time since we started the surveys, student understanding and appreciation moved strongly in the right direction.

Again, this time, teaching decreased, but learning numbers improved. How could there be less teaching but more learning? Perhaps using social media is like being on a school newspaper: you express yourself in public, so are more interested in the rules that govern public expression. Or perhaps it’s simpler than that. Maybe students support freedom when it directly benefits them. They believe music lyrics and student newspapers should not be censored, for example, but don’t feel the same way about traditional print newspapers. Since a large majority of students use social media, it’s “theirs,” in the same way that music is theirs.

Many high school teachers, however, would dispute the idea that social media is a good thing. Digital natives love it; teachers, not so much. This seemed to offer another opportunity. Knight, along with the First Amendment Center and the Newseum, sponsored a college scholarship contest, “Free to Tweet” as well as a teacher’s guide to social media.

Looking beyond the classroom

What should future First Amendment surveys ask? Should we look more carefully at how teacher beliefs affect students? Or try to figure out where teachers get their skewed ideas about the First Amendment? Do their beliefs relate to demographic, geographic, ideological, educational factors, or others? Are teachers who are suspicious of digital media the same as those who don't have strong First Amendment knowledge and beliefs? If teachers used social media more, would their First Amendment attitudes and knowledge improve? Or is the whole thing much simpler than we are making it out to be: the further away society gets from a violent event like 9-11, the less we worry that our open, tolerant attitudes make us vulnerable.

All in all, put into context, the glass seems half full. First Amendment awareness and understanding among high school students appears to be increasing. High school journalism is plentiful (though mostly not on line), shows a survey by Mark Goodman, the Knight Chair in Scholastic Journalism. And the American Society of News Editors-led Sunshine Week seems to have helped rally many groups to help people understand why Freedom of Information laws are important.

After 9-11, FOI laws were rolled back. That trend now seems to have slowed, and in some states, stopped and reversed itself. But at the national level, many argue, the current administration is less transparent than its predecessors. It may be that the seemingly unstoppable military-digital-industrial complex is the hidden source of this increased secrecy. An “FOI audit” technique I developed in California seems to confirm this. (The “audit” consists of using the freedom of information laws to, in essence, require the government to report its own performance under those laws.) The first Knight Open Government Survey showed few federal agencies following the president’s open government order, signed on his first day in office; even after a stern letter from the White House chief of staff told agencies to shape up, a second survey showed progress was still slow.

Topics like greater public awareness of freedom and the success of high school journalism might seem high-minded. But caring about them is not an academic exercise. Our work makes a difference — exactly how much of one is difficult to say. Changing the future is a tricky business. Media ecosystems are just as hard to unravel as any other kind. We can’t go back in time and see what happens if we don’t make our grants, so we make our best efforts to measure and predict.

Projects like Knight’s high school initiative had enough value to draw strong partners, like Reynolds Foundation. Others, like the News Literacy Project, put together local funding packages. Some projects had strong matching funds from schools themselves and were continued by government, such as Prime Movers in Philadelphia.

We helped several groups raise endowments, including Student Press Law Center, which fights for student journalists; the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which defends all American journalists and the Committee to Protect Journalists, a champion of journalists worldwide. We joined with the Poynter Institute to create News University, now with 250,000 registered users. NewsU.org is such an effective educational model, Poynter made it central to the organization. The Newseum, the world’s only major museum of news, donated games to NewsU that teach the importance of news and the First Amendment to thousands of students every year. Sunshine Week has provided open government news stories read by millions of Americans.

These groups publish lengthy lists of accomplishments. They free news organizations, improve journalism, keep people out of jail and save lives. But the overall trends they seek to shift — excellence in journalism and journalism education, public awareness of the importance of journalism and open government — are moving targets, often pushed by much larger forces than foundation grants. Efforts to increase diversity in commercial news organizations, for example, smashed into what may be a permanent economic brick wall. As the book News in a New America explains, when traditional news organizations grew and made money, they increased diversity. Today, as the organizations shrink, so does newsroom diversity (which may then push the community away and increase the rate of the news organization’s shrinkage). Newsroom training is in a similar position, shrinking with the news outlets.

Despite the uncertainties, we keep trying. We plan to continue the First Amendment research with our collaborator, Dr. Kenneth Dautrich, a senior researcher at The Pert Group and professor at the University of Connecticut. Dautrich, who has worked with us since the start, co-authored a 2008 book, “The Future of the First Amendment,” about the first two surveys. I continue to wonder about out-of-classroom alternatives. Are social networks and games legitimate alternatives to traditional classroom work? In the 21st century, it seems harder to improve classroom teaching than it is to create a popular game or YouTube video. This, too, is a rich area to explore. We’ve done some early work on educational games, technology for innovation and digital media literacy, partly in connection with strengthening libraries in Knight Communities.

The Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities has recommended that digital media literacy be incorporated at every grade level. (Digital media literacy certainly includes First Amendment education, along with civic, news, media and digital literacies.) Our grantees have called for universal digital literacy at standard-setting groups, teacher colleges and testing institutions. Including the First Amendment under the umbrella of digital media literacy can offer another pathway for educators. In recent years, we have experimented with news literacy at Stony Brook in New York and digital media literacy at Queens University in Charlotte. Perhaps these projects will demonstrate the democratic, educational and economic benefits of 21st century literacy.

A good portion of Knight Foundation’s work involves starting new things. This isn’t usually how people think about government or foundation funding. Many do good work by doing what we would call charity: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day.” Foundations call their work

When you look at venture capital successes in starting digital media businesses, venture philanthropy doesn’t seem all that bold. Just think of how digital media has changed since the first Future of the First Amendment survey: Facebook, if it were a nation, would be the third largest in the world. Then Twitter came along, and people across this planet, it seems, tweet more than all the birds. The younger generation, the digital natives of this social, mobile media world, seem to have a greater appreciation for the freedoms that make it all possible — much greater than the high school students who came before. To me, it’s a hopeful sign that these new digital tools can amplify the best in us.

The original version of this post appeared in the Knight blog.

How the Challenge Fund

for Journalism

helped nonprofits

weather the recession

I’ve written about how during the past decade, journalism funders have been finding more and better ways to work together. During the past seven years, for example, we teamed with others to help journalism nonprofits develop better business practices through a project called the Challenge Fund for Journalism.

A recent study of the Fund showed how it helped 53 journalism nonprofits, both professional organizations and media outlets. The fund’s partners were Ford, which created the project, as well as Knight, McCormick, and Ethics and Excellence in Journalism. The management consulting firm TCC Group coordinated.

Some organizations, usually the smallest, got fundraising and administrative training only. Others got training as well as a grant that they could collect only if they could raise twice as much funding by themselves. That’s like giving away a fish if someone can catch at least two more on their own. Hence, the name of the report, “Learning To Fish.” As noted before, the largest amount of philanthropic money given away each year in the U.S. comes not from foundations, but from individuals. The challenge fund helped nonprofit journalism groups learn to fish where most of the fish really live.

The foundations put in $3.6 million, and the grantees found nearly $9.5 million in matches. Nine in 10 made their matching goal. In addition, 85 percent said they experienced positive organizational change as a result of the project. The groups that did the best realized that “business as usual” was no longer an option. They appealed to individual donors and broadened their foundation requests to include grant-makers who care about the issues journalists cover, such as civil society or public health. They built new firewalls so certain types of no-strings corporate grants would be allowable.

The International Center for Journalists, for example, doubled revenue from planned gifts and bequests between 2009 and 2012. The Center for Public Integrity ramped up efforts and revenues from individual donors. Investigative Reporters and Editors diversified its revenue streams.

Obviously, the better a group is at delivering the goods, the better its fundraising position. TCC’s coaching, peer meetings and other efforts helped the organizations during a time of “drastic upheaval,” as Ford’s Calvin Sims put it, that caused regular sources to dry up. Said Andy Hall, Executive Director of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism: “The greatest value of the initiative was that it enabled us to try out new strategies for growth, which ultimately helped change our business model.” The center added board members who knew how to raise money. It expanded its corporate sponsorships, and introduced new fundraising events.

Too often we take for granted the important role nonprofits play in training and professionalism, or, as Bob Ross of Ethics and Excellence puts it, “maintaining a vibrant journalism sector.” That’s why Clark Bell of the McCormick Foundation is right when he says that, these days, even “healthy organizations have to be willing to revisit and overhaul their business models.”

After this post appeared in Knight blog, journalism funders began discussing a follow-up project, a Challenge Fund for Journalism Education, that would offer micro-grants to universities that develop “teaching hospital” experiments.

Clearer writing means

wiser grant making

Clarity matters. That seems obvious. Yet in our nation’s capital, when the Sunlight Foundation released a 2012 study measuring how well lawmakers communicate, we learned that even clarity can be controversial.

Sunlight found that members of Congress have made a big leap these past seven years in their ability to talk clearly. You would think all would jump for joy. We want open government. Clear talk is more accessible than jargon. But no. Sunlight’s news release — and most of the news coverage — took a different tack. They asked: “Is Congress getting dumber or just more plainspoken?”

That’s just wrong, and it brings into focus a big issue for foundations.

Too often, we fall into the trap of thinking complex communication equals intelligence. Fancy words mean you’re smart; simple words mean you’re dumb. Because my foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, was founded by two of America’s leading newspapermen, we think about this topic a lot. We believe you have to be smart to convey difficult subjects with clarity. If you can do it, your work will be more effective.

To measure Congress, Sunlight used something called the Flesch score. Rudolf Flesch, author of Why Johnny Can’t Read — And What You Can Do About It, created this measure of readability. The higher your Flesh score, the clearer your writing. The clearer you are, the more people you reach.

Let’s test the Flesch score of a classic children’s song:

Three blind mice

Three blind mice

See how they run

See how they run

They all ran after the farmer’s wife

Who cut off their tails with a carving knife

Have you ever seen such a sight in your life

As three blind mice?

Run a spell check in Microsoft Word, and if your settings are right, a Flesch score will pop up. Without line breaks, “Three Blind Mice” scores a nifty Flesch of 70. No wonder everyone understands it.

Yet too many writers at too many foundations would feel compelled to change this simple song by layering on foundation-speak. It would go more like this:

Three rodents with defective visual perception

Three rodents with defective visual perception

Visualize how they perambulate

Visualize how they perambulate

They all perambulated after the agricultural spouse

Who severed their appendages with a kitchen utensil

Have you ever visualized such a spectacle in your existence

As three rodents with defective visual perception?

On a scale of 0 to 100, that scores a Flesch 0. Unlike Coke Zero, Flesch 0 is a bad thing. Too often, this is how we in philanthropy talk and write. We litter our prose with jargon. Our message becomes vague. Truly, how can we expect to help people if they can’t understand us?

At the Knight Foundation, our mission is to advance “informed and engaged communities.” That can’t happen without clarity. So we use the Flesch score. We try to keep our internal documents at a Flesch 30 or higher; our press releases, Flesch 40; our speeches, Flesch 50. Since any readability test is only a rough measure, we don’t sweat decimal points. Numbers rounded off are fine.

Knight is certainly not the only foundation that believes you must speak to a society to help improve it. Michael Bailin, president of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, wrote: “The real threat of unclear language is its power to extinguish thoughtful public discourse.”

Indeed. How can we expect a community to act on a study if only a few Ph.D.s can understand it?

Clarity strengthens discourse

Even worse, noted Tony Proscio, author of “Bad Words for Good,” is what folks do when they don’t understand: “People who can’t puzzle out your real meaning will soon draw their own inferences about it.” That’s right. We remember in narratives. If a story has a hole, we fill in the missing piece, using our imaginations when we don’t have any facts.

After a dozen years of grant making, I’ve learned, sometimes the hard way, that clarity does matter. When the writing is clear, we understand each other. Paperwork moves faster. Questions are fewer and smarter. Discussion is richer. The money we give away achieves more. People know what they are trying to do and why. Clear writing allows all parties to get on the same page and move in the same direction. Think about a grant as a common dream of a better future. Clear writing helps us dream together.

It can be fun. At Knight Foundation, we run seminars like “Writing Tips and Tricks.” Mary Ann Hogan sometimes helps us out as a writing coach. Not long ago we gathered at lunchtime to play “Jargon Jeopardy,” a version of the game show that rewarded clarity. During the game, the tired foundation word “stakeholder” came up. The host (me) joked that the only stakeholder who lived up to the title was Buffy the Vampire Slayer. She not only held stakes but plunged them into the hearts of the undead. I wish I could do that to some of the news releases foundations put out.

Federal agencies have been urged to keep their writing simple. Under the new Plain Writing Act, officials must communicate more clearly with the public — use the active voice, avoid double negatives, favor personal pronouns, and run the other way if someone says “incentivizing.”

The nonprofit Center for Plain Language, founded for federal workers, gives awards for the best and worst of government-speak, including a “turnaround” prize for the most improved agency.

The average American communicates at about an 8th-grade level. That does not mean America is in the 8th grade. It means only that we prefer a level of clarity that can be understood by everyone all the way down to the 8th grade. Congress is now talking at a grade level that reaches down to the 10th grade; it used to be the 11th. So its members got a little clearer — to answer Sunlight’s question, they became more “plainspoken.” They may or may not be dumber. That’s an entirely different question.

If you ask me, Congress is still not clear enough. There’s still a lot of “Three Rodents with Defective Visual Perception” going on in Washington. (That version of the song, by the way, scores at Grade 28. It’s pretty easy to hide what you’re really doing if no one can understand you.)

Of course, clarity doesn’t equal truth. But it helps. Though Sunlight was wrong to equate simple words with simplemindedness, it still did two good things:

First, it raised the issue. Second, it called attention to a useful new website: capitolwords.org. The site is a gift of the digital age. You can type in a word and see who said it in Congress, when, and why. You can see which words members most used each day, track their usage over time, and see which words your congressperson used most. You can even type in “clarity” to see what kind of debate Sunlight created with its study.

The holy book of clear writers, The Elements of Style, offers this wisdom: “Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.”

What is the penalty, in foundation work, for writing that does not make every word tell? We waste money that isn’t ours to waste.

I remember years ago looking at a report from a longtime grantee. The project was to get young people into a certain career. After a decade, and much expense, not one young person who had gone through the program had gotten into that profession. I looked carefully at the reports and at our grant documents. The grantee’s work fell within the language of the grant. But the grant never set a clear goal. Talk about “defective visual perception.”

If I could wave a magic wand: Grantees would help edit foundation paperwork about their projects. Grant write-ups (our internal summaries) would be so clear they could be news releases. Grantee reports would be so honest you could put them right online. Grantees would blog their benchmarks. The foundation would speak clearly and candidly not only about what it has done, but about what it’s thinking of doing and why.

How do you make these changes? One word at a time. So, when you next look down at the sentence in a grant write-up that says, “The primary stakeholder will operationalize the leverage so they can scale their sustainability infrastructure,” don’t panic. Just please change it to

“They will hire a fundraiser.”

After this piece (Flesch score 68) was published by the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Knight Foundation gave a grant for Project Madison, a tool to help the public write legislation.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful for the digital age itself, because it bounced me from editing newspapers (journalism’s present) to creating a news museum (journalism’s past) to working with Knight Foundation’s extraordinary group of people to fund media innovation (journalism’s future.)

Everyone at the Foundation helps with the work. There’s no way to thank one without thanking them all. But don’t just take my word for it…

At the Plaza ballroom in New York City in the summer of 2012, Knight Foundation won the Syracuse University i-3 award. It stands for “influence, impact and innovation” and goes to an organization or individual who has captured the public's imagination about what media can do. CNN and YouTube won for bringing video to presidential debates; Blue State Digital for changing political campaigns, and Foursquare for linking cyberspace to physical space.

ABC TV host, anchor and political journalist George Stephanopoulos presented the award. Here’s what he said: “This year, for the first time, a foundation has won the i-3 award — the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation of Miami, Florida — for redefining the role philanthropy can play in media innovation.

‘… No journalism grant-maker today has the influence of Knight. When I host ‘This Week’ from Washington, I do it from the Knight Studio at the Newseum. When I recognize courageous global journalists at the International Center for Journalists, there’s Knight again, as that organization’s largest, longest funder. Knight brings its digital edge to many different programs — it has a network of endowed journalism chairs and training programs, reaching thousands of students and professionals, and the best-known e-learning … Knight funded Sunshine Week to fight for freedom of information. Knight’s report on the Information Needs of Communities sparked the FCC’s interest in that issue.

“Knight Foundation stands for informed and engaged communities. Its impact in communities provides better access to broadband, improved digital and media literacy, new tools to engage people in civic affairs and even new ways to start nonprofit news organizations. Its Knight Community Information Challenge has brought hundreds of community foundations into news and information grant-making. The Carnegie Knight Initiative for the Future of Journalism education has helped leading journalism schools change the way they teach in the digital age.

“Early on, the Knight Foundation created a contest to spur media innovation, the Knight News Challenge, which has produced tools and techniques now used by hundreds of newsrooms and thousands of journalists. The news challenge showed that anyone, from 20-something computer programmers to the staff of the Associated Press, can and should try to shape the future of news. At a time when many devalue journalism, Knight’s open "R&D" helps both the profit and nonprofit sectors come face to face with journalism’s future.”

That’s quite a tribute. I don’t see how it would have been possible without the foundation’s hard-working staff and forward-thinking trustees.

Special thanks to our president, Alberto Ibargüen, the skeptical optimist who challenges and encourages our work, and our vice president for journalism and media innovation, Michael Maness, who pushed me to write further into the future of news. Thanks to former vice president Paula Lynn Ellis, who helped the foundation reform itself, and Knight program associate Marie Gilot, whose edits came at lightning speed, right on deadline, as well as Michele McLellan and Maria Mann, journalists and friends who read the manuscript and made many helpful suggestions.

Mary Ann Hogan, my writing coach and spouse, helped me tune and tone. Interns Romina Herrera and Katrina Bruno of Florida International University researched, wrote and edited, as did program assistant Luis Linares and administrative assistant Lauren Rothstein, who compiled “books to read.” Creative director Eric Cade Schoenborn and designer Chris Rosenthal are responsible for everything that looks good about the project’s responsively designed HTML 5 website. Michael Bolden, Marika Lynch and Elizabeth Miller from our communications team made my Knight Blog posts, the press materials and this book coherent, as did our contract copy editor Connie Ogle. Andrew Sherry, vice president of communications, pushed the project from day one.

Midway through the project, the University of Missouri’s Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute offered me a fellowship to help develop the book’s “learning layer,” which we hope will help teachers who care about the digital transformation of journalism education bring these ideas into the classroom. Thanks to Dean Mills, dean of the Missouri School of Journalism, home to the oldest and largest “teaching hospital” model of journalism education, for the opportunity. Thanks also to Reynolds executive director Randy Picht and Roger Gafke, professor emeritus and director of program development, who coordinated the Institute’s contribution.

Reynolds selected a helpful team of graduate students, researchers and educators to produce the classroom activities and suggested assignments, readings and research. They are: Mark Goodman, Professor and Knight Chair in Scholastic Journalism at Kent State University; Cathy Collins of Massachusetts, a certified library/media teacher and journalism educator; Ruben Valadez, journalism/photojournalism teacher at Eagle Pass High School in Southwest Texas; Judd Slivka, consultant and former director of information services at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources; Mimi Wiggins Perreault, doctoral student and Huggins Fellow in the University of Missouri School of Journalism; Greg Perreault, journalist and Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Missouri; Adam Maksl, assistant professor of journalism at Indiana University Southeast. Their full bios appear on the Reynolds Institute web site.

Their contributions were too many to detail. As the primary author and editor, however, the responsibility for any errors or omissions is mine.

About the author

Eric Newton, senior adviser to the president at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, joined the foundation in 2001. As journalism program director and then vice president for journalism and media innovation, he oversaw the development of more than $300 million in grants and helped build the department from a one-person operation into a team of seven.

Before joining Knight, Newton was founding managing editor of the Newseum, the world's first museum of news. He started at California newspapers. As managing editor of the Oakland Tribune under Bob and Nancy Maynard, he helped the paper win 150 awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, and co-founded the First Amendment Project, a nonprofit law project.

His best-known books are Crusaders, Scoundrels, Journalists and The Pulitzer Prize Photographs: Capture the Moment, the latter still touring after a decade as a traveling exhibit. Named a distinguished alumnus of San Francisco State University, where he earned a BA in journalism, he became a Rotary International Scholar at the University of Birmingham, England, where he was awarded an MA in international studies. He has taught journalism at all levels.

Newton shared a Peabody Award for Link TV’s "Mosaic: World News from the Middle East," which ran from 2001 to 2012. He won the Reddick Award at the University of Texas for service to the field of communications, the RTDNA First Amendment Award for Sunshine Week and the Markoff Award at the University of California, Berkeley for support of investigative reporting.

Let us know what you think

Just as we consume too much comfort food, we are, more and more, consuming “comfort news.”

ISBN# 978-0-9749702-4-0

Introduction | Chapter one | Chapter one, part two

Chapter 2 | Chapter three | Chapter four | Chapter five

Site directory

Site directory

Learning layer directory

Learning layer directory

Searchlights and Sunglasses: Field notes from the digital age of journalism by Eric Newton is licensed

Searchlights and Sunglasses: Field notes from the digital age of journalism by Eric Newton is licensedunder a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Learn more about this project.

Read how the book supports Common Core Standards.

We'd love to hear from you.

Download the book in the .epub format

Download the book in the .mobi format

Download the book in the .pdf format